Take a ride on the Kinder Carousel! Train your intermediate grade-level leaders! Watch them grow in confidence, instil the spirit of discovery and empower your all Kinders to express their wonderful thinking in new ways. STEM powered and LEGO® inspired, read on to see the fantastic results of this perfect pairing.

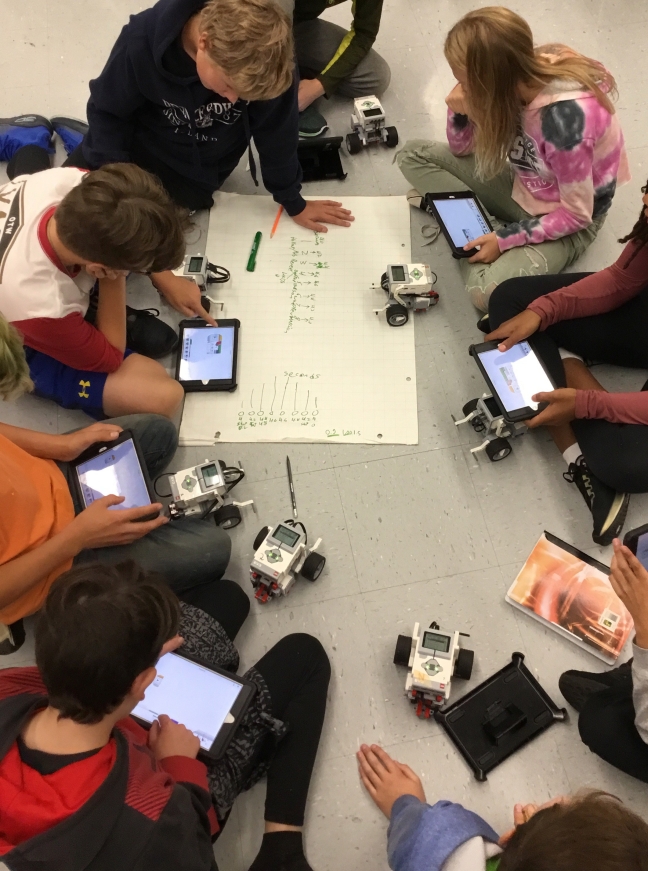

All facilitators need opportunities to apply and refine their practice by repeating the same exercise multiple times to gain new insights and better questioning techniques to bring out the best from those participating. As we prepare our students to be leaders of tomorrow, they must have the opportunity to be the leaders of today. Working with kindergarten teacher Katherine Macleod, we co-created a number of simple carousel style LEGO® centres, targeting specific learning expectations for her students, as well as giving our grade seven leaders an opportunity to present, observe and adapt their own approaches to become better facilitators.

Learning, in so many ways, is a conversation; an exchange of ideas and sprinkled with gentle encouragements to take the risk and explore. When given the opportunity to build a one-on-one relationship with a student facilitator, children are better able to express their own learning and to playfully explore a variety of possible solutions. Throughout the activity, many kindergarten students communicated ideas or did tasks never before seen in the regular classroom setting. When observing some students emerge out of their shell behaviourally and socially, Early Childhood Educator Lisa Froom remarked several times that particular students would have never made such profound leaps without their grade seven mentors. Conversely, after receiving many hugs from the kindergarten students and hearing the impact that their efforts had made, the grade seven students beamed with pride, gained confidence and felt the satisfaction that only comes with authentic mentorship.

These powerful pairings unlock learning.

What did we do?

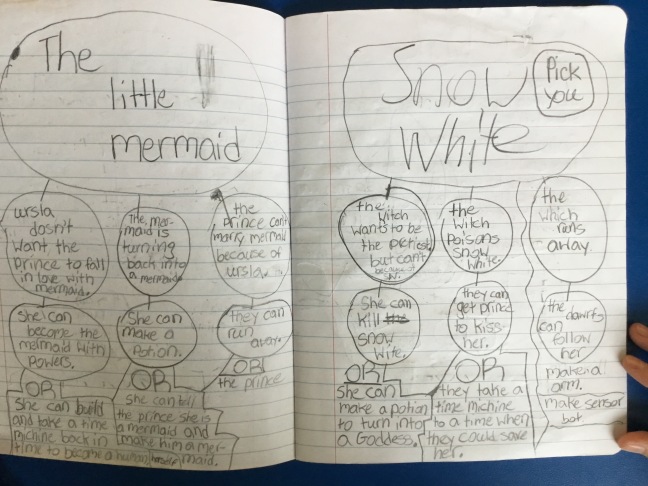

Four teams were tasked with facilitating one 10 minute learning experience station, four times in a row. Each station focused on different kindergarten skill sets and competencies. With back-to-back sessions, the grade seven facilitators could better identify what worked and make continual improvements to the instructions, promptings and one-on-one relationship building techniques. I was careful to observe each team. During transition times, I would help the students identify any gaps in the instructions or suggest alternative prompting questions before the next group arrived. The foundation of authentic student leadership is that they facilitate the learning and are to not direct it. Our facilitators are encouraged to ask probing questions; getting students to clarify and to explain their thinking. This framework of facilitation acts as a sounding board for students, allowing them to better understand their own thinking and see alternative solutions or perspectives. It also allowed for plenty of pedagogical documentation by staff members who could, from a distance, observe and record many moments of student growth without interrupting the learning journey.

The Stations

Free Build: Allowing students to be inspired by a massive pile of LEGO® bricks will lead to amazing creations. With an overwhelming amount of pieces to inspire, many students may enter the build with preconceived goals of, let’s say, building a car. However, the act of picking up pieces actually inspires new ideas; rapid wonderings how a LEGO® element may fit in or possibly take the build in new directions. The LEGO SERIOUS Play® adage is, if you don’t know what to build, just start building. Many are unaware of this powerful process, that in the act of building and touching LEGO®, new ideas, perspectives and solutions are formed. Who would have thought that playing with LEGO® could generate new ideas, not simply represent cars, trucks and bridges? Click here for more reading on this subject and how we use LEGO SERIOUS Play® in our practice. Many of the articles we’ve posted speak directly to this and its tremendous benefits.

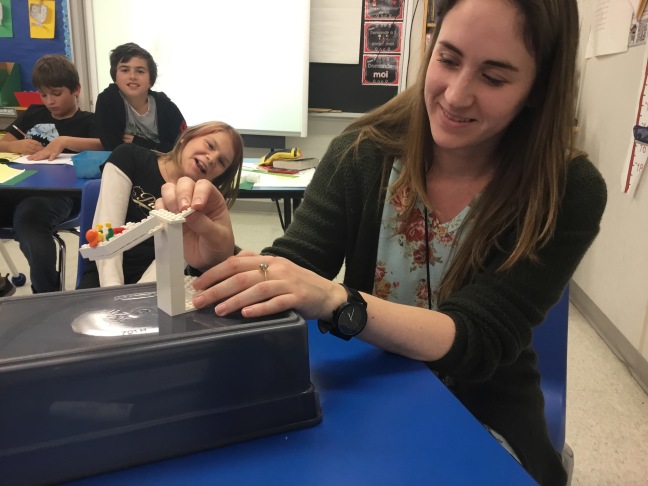

Tower Build: A go-to LEGO® challenge with a lot of opportunities for learning. LEGO® towers will all fall the taller they go. This centre gives many opportunities to try, test and modify solutions. The grade seven leader is there to slow down the experimental process, discussing what they want to try, what they observed and how they could improve their tower. Child-sized adversity is the flavour of this station, continual fails, successes and modifying the goals to make it more challenging (just how high can you go? How strong can you make it? Can you accomplish the same goal with fewer LEGO® pieces?).

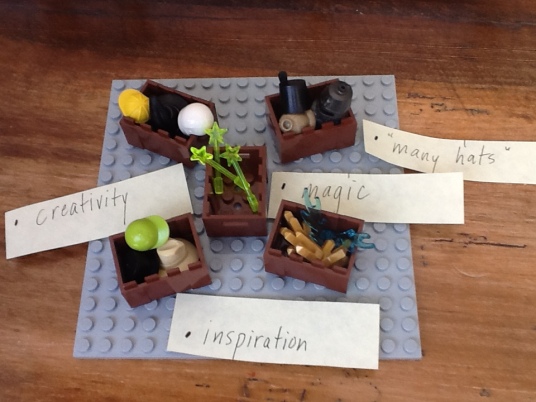

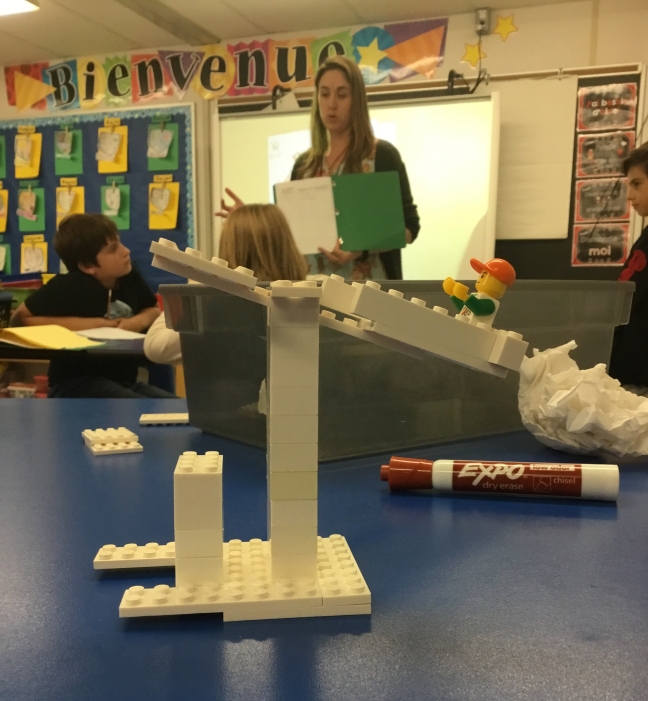

The Duck: We spend a lot of time helping students to represent their ideas using LEGO®. The first step any student must take is is overcoming the false belief that any build must perfectly look like the object being representing. Before building, students picture all of the features of any given object…but it is simply impossible to capture the totality of features using a brick. So, we teach the kids to show us the features they are able to represent using LEGO® and to use their explanations to fill in the rest. This liberation from a perfect representation always leads to rich discussion. To unlock this new perspective, we begin with constructing a duck (this is the go-to startup activity for any LEGO SERIOUS Play® workshop).

The students are quick to represent the physical features of the duck, sharing their creation with their peers along the way. The student facilitators then ask questions about the features not represented by the LEGO® model, such as feathers, webbed feet, a duck quack. We discuss the similarities and differences between the ducks in our pond. It is important to ask questions like: “Can you tell me about your model? or “What does this part represent to you?”. Even at this very young age, it is so important that students take pride in their creations and have the freedom to explain away any missing features. It is also beneficial to allow students to interpret the build of others, asking questions like: “What features of a duck do you see on this model?”. With this form of flexible representation, any student has the freedom to represent the even most abstract of ideas into tangible creations.

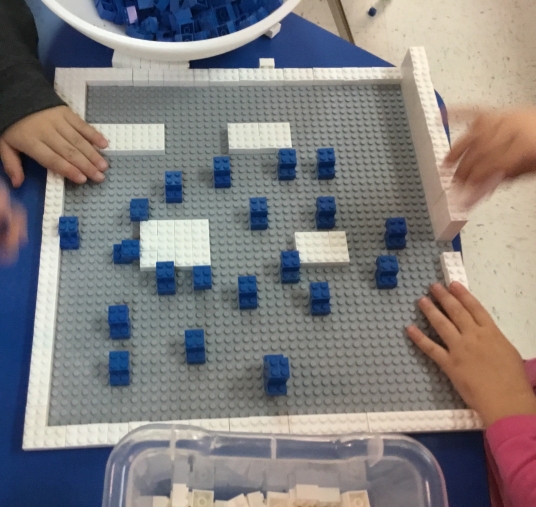

Build a Copy: This station challenged kindergarten students to build a copy of a basic LEGO® model. The grade seven students would build a creation using a few LEGO® bricks and the Kindergarten would build a duplicate. The grade seven facilitators quickly realized the importance of building a simple model first and gradually increasing the complexity of the model. Kindergarten students got a kick out of trading roles; they got to build a simple LEGO® model and the grade seven had to build a copy. Some kindergarten students focused on the colours matching while others focused on the pieces used. Some amazing discussions were observed, especially when the kindergarten student was asked to explain the similarities and differences between the two models. The number of and type of LEGO® pieces used, colour comparisons, and actual construction were all possible points of discussion.

Only lasting one hour, the impacts on both age groups was very apparent. We gained so many new insights about all of our students, their learning and their potential. With very little work, you too can bring the carousel into your classroom today; prepare to be amazed!